Closing the loop: How to recycle aircraft batteries

Making aviation truly sustainable is a long-term challenge that will take decades of innovation, collaboration and investment. While solutions like sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and next-generation electric and hydrogen aircraft are making headlines, one area remains underexplored yet full of potential: recycling.

In this first article of a new series, Aethos takes a closer look at the opportunities and hurdles of aircraft recycling, starting with batteries. What types of batteries are used in aviation today? How recyclable are they? And what complexities stand in the way of closing the loop?

Batteries used in aircraft

Aircraft rely on a range of batteries to power various devices. Chief among them are the main batteries that start up the auxiliary power unit (APU), which then starts the systems and the engines; and the batteries that supply emergency power for critical equipment and flight control instruments. Of equal importance are the applications commonly known as the ‘black box’: flight data recorders (FDR) and cockpit voice recorders (CVR).

Inspired by the rise of electric cars and drones, the aviation industry also has a drive to develop batteries that will eventually be able to power whole airplanes. Electric flying is as yet only realised for small two-seater aircrafts on short-haul flights or lessons – but it is likely to gain traction in the near future, as the technology advances.

Recycling aircraft batteries: One size fits none

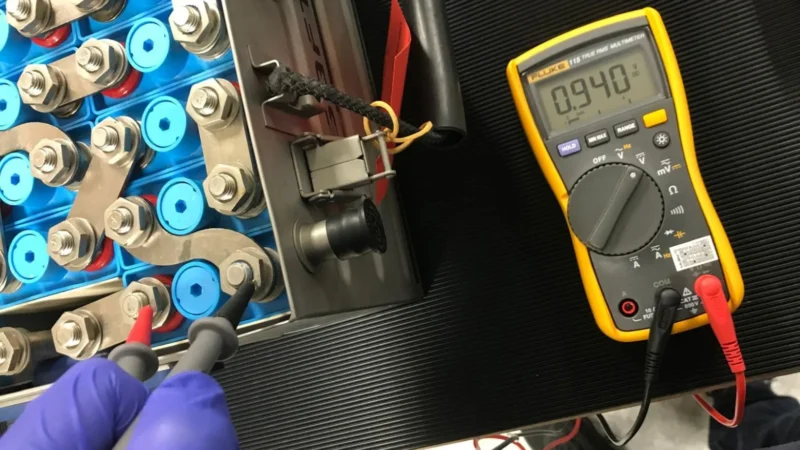

As a rule, batteries used in aircraft are highly customised to ensure maximum safety and reliability, while also delivering a high energy output at a low weight. Hence, no battery is the same. Because of this, recycling them is never straightforward. There are many different kinds of battery cells, modules and packs, using different materials and cell chemistries, requiring different recycling methods.

To complicate matters further, a battery comes with many additional components using a range of materials. Think of casings (stainless steel, titanium, plastic), connections and current collectors (copper, nickel-plated copper, aluminium), electrolyte (salt solutions, organic fluids, acid), cathode active materials (lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, iron phosphate, lead) as well as plastics for several purposes.

Handle with caution: How to dispose of batteries

It is no surprise, then, that recycling batteries is a task for specialised companies, in the form of acknowledged, Part 145-certified MRO shops. In addition, the US, China and the EU have introduced laws and regulations that increasingly make battery manufacturers in any industry responsible for collecting used batteries and ensuring sustainable processing, as well as reporting on their results.

In general, these facilities have two main recycling processes to choose from, both with their own advantages and drawbacks. The traditional approach is the pyrometallurgical process, using high temperatures to recover metals. It can be used for many types of batteries, both older and newer (lead-acid (Pb-acid), nickel-cadmium (NiCd), nickel metal-hydride (NiMh), lithium-ion (Li-ion)), without pre-treatment. However, it requires high energy use, its product recovery is limited, and resulting materials need further refining.

For newer types of batteries (NiMh and Li-ion), the alternative is a hydrometallurgical process, using aqueous solutions to dissolve and separate metals. Although still maturing, this process offers a lot more product recovery, producing higher purity materials. The downsides are the need for pre-treatment and the high use of chemicals, which requires extensive liquid waste management. First generation sulphate hydro-processes in particular produce lots of sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), highly soluble in water, which amounts to a very unsustainable 1kg of waste for every kg of battery. Fortunately, the next generation of hydrometallurgical technology has found a way around this.

Due to the high cost and complexity of developing and certifying new technology, the aviation industry tends to continue using older battery types (Pb-acid, NiCd). Vested interests of the manufacturers of this technology also present a barrier to the wider adoption of newer, cleaner alternatives.

Beyond recycling: Black box batteries

Many batteries used in aircraft can be recycled. Notable exceptions are the batteries used for emergency applications, such as FDRs and CVRs. To ensure their functioning under extreme conditions they run on non-rechargeable Li-metal batteries, for which there are as yet no sustainable recycling options available. Sadly, this means that end-of-life batteries are piling up in expensive containers specifically designed to mitigate the risks associated with storage of these batteries.

The future of battery recycling

Batteries play an important role in the energy transition and could become a major factor in the circular, emission-free aviation of the future. What can we do now to make this a reality?

Raising awareness is always a valuable first step. Do you know what your MRO organisation does with batteries that are beyond economical repair (BER) – when repairing them costs more than sourcing a new battery or battery section? The more industry professionals understand the available options, the better positioned they are to drive meaningful change.

OEMs such as SAFT also bear a responsibility to encourage a more sustainable approach to batteries, for instance by relaxing regulations in the component maintenance manual that currently favour replacing a battery when some cells are still functional. Another step might be to lower the price for individual cells, which makes revising a battery cheaper than replacing it.

Ideally, recycling where possible will become a standard requirement. Considering the budding ascent of electric aircraft, now is the time to make sure there are solutions in place for the current batteries before large volumes reach their end-of-life.

This article is based on a recent study into the recycling of aircraft batteries, commissioned by Aethos. The full study is available here.

Aethos is a foundation committed to advancing recycling efforts in aviation. Founded by Derk-Jan van Heerden, former chief executive of aircraft disassembly company AELS and former president of the branch organisation AFRA, it supports research and innovation in the field of material recycling from retired aircraft and components that are beyond reuse and repurposing.